Idaho Falls - City of Destiny

CHAPTER 1

Agriculture and Canals

Surrounded by Russets

Idaho Falls is surrounded by a special kind of farm land which contributes significantly to the production of the world's most famous potato. The soils and climatic conditions of the Snake River plain are ideally suited for the crop which made Idaho famous. Potatoes grow best at high altitudes during long, warm summer days and cool nights. Irrigation water from Idaho's mountain streams makes it possible to precisely control the amount of water required to produce an ideal crop. The ash left by volcanic eruptions millions of years ago created light soils and deposited important trace minerals apparently needed for the production of a super potato.

Although there are more than 2,000 potato species under the Solanum genus, eight of which are grown by man, almost all of the potatoes grown in our state are of one variety, the Russet Burbank, affectionately known as the "Idaho Russet." Originally developed by Luther Burbank in 1872 from a single seed ball growing in his New England garden, this new variety would produce two or three times more than other common varieties. Lon D. Sweet from Denver, Colorado selected a sprout out of the original Burbank seed tubers which had a rough or russeted skin; and this seed eventually found its way to Idaho. The new elongated potato was high in solid content, had a mealy white fluffy texture and a pleasing flavor - the ideal baking potato.

It is not known exacly when or by whom the first Sweet's Burbank Russet seed was brought to Idaho, but for a period of years Idaho was the only state growing Russet Burbanks and soon gained worldwide fame. Attempts were later made to grow the Russet in other areas, and it is now grown in Washington, Oregon, Maine, Colorado, Michigan and Wisconsin. Idaho potato experts continue to maintain, however, that no state can match the ideal growing conditions in Idaho, and so the tradition of the wonderful Idaho baker piled high with sour cream and melting butter continues.

In the early years, potatoes were planted by hand in furrows made by walking plows pulled by horses. They were dug with shaker plows, and later by one row horse-drawn diggers, and then picked, bagged, and hauled to sell, or placed in cellars. In the gold mining days, potatoes were hauled to Caribou mountain to be fed to the Chinese miners.

Picking Spuds. For the school children of Idaho Falls until the 1950's, there was no task more solemn to perform in the Fall than to help the farmers get their potato crop in. Schools were dismissed for "spud vacation." They were joined by housewives, anxious to earn a few extra dollars, and by migrant workers from Mexico. The two weeks spud harvest vacation took place after the frost killed the potato vines, usually in early October. The potatoes had to be dug and picked up as soon as possible because more heavy frost would go deeper into the ground and kill the potatoes. During cold years it was not uncommon for farmers to leave part of their crop frozen in the ground.

Pickers would arrive in the field often before sun-up. They would usually work in pairs, each having a wire basket. The best pickers could average over 200 sacks a day, and the fastest pickers often seemed o be women. Two filled baskets would be emptied into a "halfsack," a burlap bag, picked from those scattered along the rows by the farmer. Pickers received seven cents a halfsack during the 1950's. It seemed to be the same rate on every farm, but one hoped for a field with big potatoes and with few weeds and clods. The work was backbreaking; partners would take turns holding the sack while the other dumped the baskets. It was an unpleasant experience to get one's glove gooey from unknowingly picking up a rotten potato, then to have the misery compounded by the thistles which more easily pierced the wet glove. Pranks abounded in the fields among the kids. They paused for clod fights to break the boredom, and rocks were sometimes placed into the bottoms of sacks to provide a heavy lift for the "buckers," teenaged boys who loaded the sacks onto the horsedrawn wagons. Sometimes tumble weeds were placed into the bags, with a few spuds on top, to further deceive and irritate the buckers.

Pickers had to be careful not to be stepped on by the draft horses or run over by the tractors or trucks. The late 1940's and early 1950's saw the last use of draft horses in the potato harvest. Many can still remember the wet burlap cloth placed around the horse's nose to help keep flies away. The farmer would sometimes let city kids sit atop one of those hugh marvelous creatures while they rested.

Modern combines and other equipment made possible a quicker and more efficient harvest of potatoes. New equipment and deep well irrigation have greatly expanded potato acreage. It has been estimated that in 1882 only about 2,000 acres of potatoes were produced in Idaho; in 1988, 350,000 acres were grown.

Processing. In recent years great progress has been made in the processing of potatoes and in developing new uses for the Idaho Russet. Most of the processing innovation has taken place in Idaho, and some of the most important "firsts" actually took place in Idaho Falls. World War II food demands led to the dehydration of potatoes, and the J.R. Simplot Co. produced the first frozen french fries. These were fries that had been frozen, thawed out and then reconstituted. Today only about half of the average truck-load of potatoes coming out of a field would end up fresh in the supermarket or in restaurants. The rest are in snack packages, such as potato chips, or in sliced potato casseroles, or made into granules, flakes, or other products. Potatoes have even been used to make gasoline and vodka. Here are some of the "firsts" in potato processing that took place in Idaho Falls: potato flour (Roger Brothers), potato dice (Roger Brothers), dried hash browns (Roger Brothers), dehydrofrozen chunks (Idaho Potato Growers), toaster hash brown (Miles Willard Co.).

Submitter: Linden B. Bateman

Grain Producers

Idaho Falls began as a trading post and developed into a distribution post when the railroad came to Eagle Rock in 1879. Until the 1950s when the INEL located in the desert west of Idaho Falls, agriculture was the main economic factor of the area. The city was the main supplier of food, supplies, equipment and repairs, plus the market place for the agriculture community surrounding the city. Idaho Falls still serves as a food-processing center for farms in the Snake River Valley. Large potato processing plants, Idaho's largest stockyards, and grain elevators are within the city limits. [Editor's note: In 1991 INEL and agriculture each accounted for about 40% of the economic base.]

Farming was the primary purpose of coming to settle in the Snake River Valley. There were a few farmers in the valley earlier, but not until 1883 did the valley see much activity in farming for a living. Early explorers and miners described this valley as one of the most hopeless spots encountered on their ox train journey across the continent.

However in the spring of 1869, Professor Hayden, who came with his geological party, spoke favorably of the Snake River Valley as a possible agriculture country. He reported the valley was "composed of a rich, sandy loam, that needs but the addition of water to render it excellent farming land."

In the late 1800s, blacksmiths, eating houses, saloons, and general stores were the beginnings of the area's economy. The agricultural economy was strengthened when crops and livestock became viable sources of income.

The Homestead Act, passed by Congress, May 20, 1862, and signed by President Abraham Lincoln, provided for any citizen of the U. S. who was the head of the family or over 21 years of age to file on 160 acres of unappropriated land and to acquire title to the same, by residing upon and cultivating it for five years and by paying such fee as was necessary for administration. "Proving up on the homestead" was a common term used by those meeting the requirements and getting title to their land.

While the land came free to the early settlers, much labor was required. There were no roads nor bridges, only the tall sage brush. To clear the land, horses were hitched to large chains and these were pulled through the sage. Then hand hoeing was required. The ground had to be plowed twice to prepare the soil for planting. The grain was broadcast by hand and harrowed in with harrows made from poles.

As fast as the land was cleared, canals and ditches were dug to bring water to the land. Wheat, barley, oats and corn were the first small grain crops planted. Every farm needed these grains at home for food for themselves and their livestock, from 1865, but in 1887, larger crops were reported and the farmers started marketing them.

Early farm implements. In the 1880s some small grain crops were harvested before "self-binders" became available. When these binders were available, two or three farmers joined together to purchase and operate one to harvest their own grain and also their neighbors' on a fee-per-acre basis. The binders, pulled by three horses, cut and bound the ripened grain into bundles or sheaves ready for threshing.

One of the first threshing machines was driven by horsepower. Six teams of horses were hitched to an upright shaft. As the teams walked in a circle, they turned a shaft which led to the separator, into which two men threw the bundles of grain. Two other men held sacks to catch the wheat. The straw was taken out on a long belt and dragged away by two horses hooked to a straw fork. One horse pulled the fork loaded with straw away from the separator while the other horse pulled the fork back into position.

Because threshing machines were costly, farmers joined together to acquire them. A number of farmers united their teams and equipment, going from farm to farm in sufficient numbers to complete each harvesting job in one operation. This group became known as the "threshers," and their annual coming was a big occasion. The women put on large feasts for these men, supplying all three meals plus treats throughout the day, as they started early and worked long after dark.

In 1892, the first steam thresher engine arrived in Idaho Falls. This soon replaced horsepower in operating the separator and was used to pull the thresher from place to place.

During the early 1900s, the construction of flour mills and sugar factories helped the population of Idaho Falls grow.

In 1991, Bonneville County was the leading barley producing county in the state of Idaho, and Bingham County was the leading wheat producing county.

Submitter: Jean Schwieder

Sources: Personal files

Lloyd Mickelsen, Idaho Falls, Idaho North Stake History

(Homestead Act).

Livestock and Livestock Auction

Livestock. In the early days of Idaho Falls, almost every family had a cow, a horse and a few chickens. Because people usually made their own dairy products, dairying got a slow start. Horses, of course, were common for sport and transportation and also provided horsepower for the farms.

In the adjacent regions cattle and sheep were grazed on thousands of acres, then shipped to markets in Chicago and Kansas City. Wool and mutton were major income sources. Livestock producers also raised hogs fed on grain and alfalfa.

Bish Jenkins, local livestock man who grew up here, recalled, "I lived on 750 `I' Street. We had a milk cow right there in the 1920s. In the late 30s they started moving corrals out of town. My Dad had a livery stable here." His family maintained two homes, one in New Sweden, and another in the city so the children could attend Riverside School. For sport the boys used to hook a good buggy horse to a surrey and race the automobiles. "We could always beat the cars into town."

The Idaho Falls Daily Post "Peace and Prosperity Edition," 1919, reported: "The great free range of the mountains and the vast forest reserves provide abundant pasturage for the grazing of cattle and sheep for the greater part of the year. While the many sugar factories throughout the valley furnish their by-products, excellent feed for cattle during the winter months.

"Due to the fact that this particular section of Idaho has grown so rapidly, the day of the great cattle man and sheep man, raising immense herds and flocks, is about over. However, there are a few who still go into this class of business on a large scale."

They name the following who graze livestock on thousands of acres in the upper valley:

The Denning and Clark Company with headquarters in Clarke County, pioneers in this industry who have made a remarkable success.

The Woods Livestock Company of Spencer, that specializes in the raising of sheep.

"Frank Reno of Idaho Falls, who owns thousands of acres of land in what is known as the Birch Creek country in the northern and western part of the valley where he has several thousand head of sheep and some of the most modern ranch buildings in the entire valley."

"The Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, which, during the past few years, has done more than anyone else in the valley, to promote the feeding of beef cattle. Through their system farmers with small capital can secure cattle for feeding purposes.... Many farmers realized much profit from their ventures in this industry.

"A. J. Stanger of Lincoln is another one of the big live stock producers of this valley. He has made a scientific study of the feeding of beef cattle, as well as sheep...Earl Wright, one of the young live stock men of the valley, has made a great success in sheep raising. He controls hundreds of acres to the east of Idaho Falls....[George C. Nielsen family,] Leo J. Nielsen and Christian Anderson of Ammon are men who have made continuous successes in the sheep raising business They also operate to the east of Idaho Falls.

"W. A. Anderson is one of the biggest operators in the live stock industry in the valley and handles yearly hundreds of head of horses and cattle....J. T. Edwards is another one who has made a phenomenal success in the sheep industry....

"Nearly every farm home has some live stock, and the farmers as a whole realize the benefit of raising the better grade of stock.

"The sheep that are raised in the Snake river valley are the best to be found anywhere, and Idaho mutton procured from this region has topped the Chicago and Kansas City markets repeatedly. Sheep and cattle are singularly free from disease and the open winters with abundant sunshine make it possible to handle these two classes of live stock at a good profit.

"Dairying industry is practically in its infancy and presents abundant opportunities. Another growing industry is that of hog raising...."

Although early butchers, such as Bennett, Brandl, and some others, slaughtered on a small scale, the city has not had a big slaughterhouse, nor meat packers.

Bees. A city brochure by the Club of Commerce of the 1910-20 period, reads, "Bee culture is claiming the entire time and attention of a number of men....Mr. J. E. Miller of Idaho Falls, several years ago recognized the possibility of this business as a revenue producer and entered upon bee culture as a side line to his regular business, that of a jeweler. So profitable did it become that he abandoned his former vocation and devotes his time exclusively to his hundreds of stands of bees. His shipments this year amounted to forty-four tons of extracted honey and this from an investment of a few hundred dollars."

Idaho Livestock Auction Company

Livestock are bought and sold in Idaho Falls by auction. The first livestock auction was held at the Idaho Livestock Auction Company on Northgate Mile August 28, 1936, and continues in 1991.

First owners were from Nebraska. F. William "Bill" Gourley was the first auctioneer. In 1937 Floyd E. Skelton moved to Idaho Falls and the next year bought an interest in the company, then bought out the Nebraska people. Other owners were Ray Skelton and Stanley Spencer, who sold out to Floyd and Leon Skelton. When Floyd died in 1987, Leon Skelton remained sole owner.

Skelton compared the business to a brokerage: "We are brokers. People from Idaho, Wyoming, and Southwest Montana consign their livestock to us to sell it. Everything is sold by auction--cattle, sheep, hogs, and horses."

Submitter: Mary Jane Fritzen

Sources: Bish Jenkins, Leon Skelton, Bonneville Museum files,

including newspaper clippings; Joe Marker, in Beautiful Bonneville

Sugar Beets. While sugar beets grow in many places in the world, they thrive particularly well in the irrigated soils of the west. Idaho, famous for its potatoes, should also be known for its sugar beets. For many years the state has ranked among the top four in the nation for the production of sugar beets. Along the Snake River from St. Anthony in the northeast to Burley in the southwest, hundreds of independent growers produced sugar beets for processing at the Idaho Falls sugar processing plant.

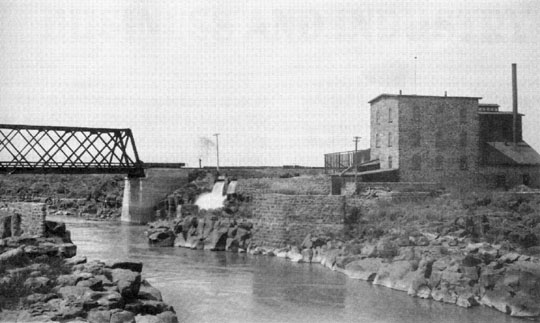

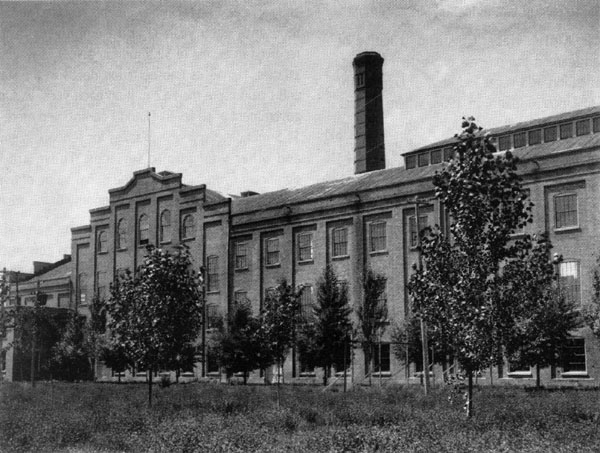

Lincoln Sugar Factory. Idaho's sugar industry began about the turn of the century. Following the success of its first sugar factory at Lehi, Utah, Utah Sugar Company, organized by the LDS (Mormon) church for the purpose of bringing in industry and a "cash" source for the area, expanded into other areas. In 1903 principals of the company and some Idaho citizens formed Idaho Sugar Company and constructed a factory at Lincoln, just east of Idaho Falls.

Heber C. Austin. Heber C. Austin, a native of England, had learned the process of western farming, including irrigation and sugar industry, in Lehi, Utah. He moved to Lincoln, Idaho, in 1903, where he was instrumental in organizing and putting into operation the Utah-Idaho Sugar Co. factory. He was named agricultural superintendent for the sugar company, helping to lay out the ground for the factory and promoting the growing of sugar beets. He helped found and build up the town of Lincoln. He was made president of the LDS Bingham Stake when its headquarters were moved to I. F. in 1908. Austin made a lasting impact on the Idaho Falls area in launching a flourishing industry, and in financial, civic and religious leadership roles as well.

Other Factories in Southeast Idaho Face Tough Times. Further expansion brought the formation of Fremont County Sugar Company with a factory constructed near Rexburg. The town grew around the factory and was called Sugar City. These two companies merged in 1905 and became the Idaho Sugar Company. They enlarged to acquire factories at Blackfoot and Nampa. The Idaho companies and Utah Sugar Company agreed to a merger resulting in the formation of Utah-Idaho Sugar Company in 1907. For a time factories were operated in Shelley and Rigby. Only the Lincoln factory survived beyond 1950.

Lincoln Factory Survives All, Strengthens Economy. The Idaho Falls (Lincoln) factory was able to survive through all the trials and surprisingly did not miss a single operating campaign in its 75 years of operation. Over the years it was repeatedly improved, enlarged, and modernized. Its original capacity of 600 tons of beets per day increased to 4400 tons, and the factory earned the distinction of being one of the most efficient plants in the industry. Over the years it produced over 4 billion pounds of top quality sugar. Under participating contracts, Idaho growers received from 14 to 16 million dollars a year from sugar beets, one of the most valuable crops in the state. U and I Inc. expended more than $4 million a year for supplies and services. Capital improvements required additional thousands each year. U and I employees in Idaho received in excess of $2.5 million a year in wages and salaries. For all its transportation needs in the state U and I paid more than $2 million each year. To support government at all levels U and I contributed more than $1.5 million every year in taxes for schools, highways and other vital public services. These are very significant figures in light of the dollar value of bygone years, and meant much to the economy of the area.

Through capable management by general and local heads of the company, operations continued in spite of the increasing cost-price squeeze. In addition to Heber C. Austin, many locally will remember the outstanding work and influence of W. J. (Jack) O'Bryant, for years the district manager of the company, and his service in the community as two-term mayor of Idaho Falls, and as a church leader.

Industry Closes. Economic factors continued to arise, however, making the production of sugar beets and sugar increasingly non-profitable for U and I Incorporated. In 1978 the management of the company announced the closure of its sugar operations and its processing plants in Idaho Falls, Garland, Utah; Moses Lake and Toppenish, Washington - the four remaining plants of a total of 17 in its 75 years of operations.

Thus ended the saga of the sugar beet industry in Eastern Idaho, a pioneer industry through the years infusing wealth, industry and color into Eastern Idaho.

Editor's note: By 1991, the factory building was gone except for the smoke stack. It was purchased by Evans Grain Company for storage and shipping of grains. They are using huge storage silos, part of the warehouse, shipping docks and storage tanks. They ship grain to the west coast on the railroad.

Submitter: W.G. Woffinden

Sources: W.G. Woffinden, personal files. He was office manger 1972-

1979.

Post Register, 7/2/76 and 7/10/80

Lloyd Mickelson, Idaho Falls, Idaho, North Stake History, c.

1982.

THE CANALS

The Utah and Northern railroad neared Eagle Rock in 1878. Young men of the work crews--some who had helped lay rails across the continent and others from the Utah settlements--eyed the level sage-grown prairie, available for the taking. Eager for opportunities, many would return to claim the promising land. Snake River valley fairly bustled in the next two decades.

Cattle ranchers Orville Buck and George Heath had planted and harvested grain in 1874 and claimed irrigation water rights on Willow Creek. All the valley needed was water, and there was plenty of that in Snake River. But "Idaho's Nile," as some liked to call it, did not overflow by itself. Homesteaders began to dig canals, but found that sweat equity was not enough. They needed supplies, capital, surveyors and legal services.

Like the land-hungry homeseekers, business people of Eagle Rock could see the boundless potential of valley farming. Some claimed big tracts to resell for quick profits with only lip service to canal projects, but a goodly number of earnest entrepreneurs devoted resources and energies to the long haul of making the desert blossom. Names well-known in Eagle Rock appear early in canal company records: H. W. Kiefer, C. C. Tautphaus, Joseph A. Clark, H. L. Rogers, J. H. Bush, C. W. Burgess, J. Ed Smith and many others. Attorney Otto E. McCutcheon served irrigation interests faithfully for many decades. Bankers contributed support, not only to Eagle Rock area endeavors, but to enterprises up and down the valley. A list of farmers who built the canals would be a veritable roll-call of pioneer families. Representative leaders included James E. Steele, C. W. Owen, David Ririe, John Empey, George P. Ward, Edmond Lovell, Hyrum Frew, Willard Moore, Eli McIntire, F. L. Brown, James Denning, S. G. Crowley, Rufus Norton, Joseph Mulliner, James Heath, Harry Groom, Joseph Olsen, Howard Andrus, Christian Anderson and of course many more.

Canal planning and building was hard, frustrating work, with failures abounding. The whole business of water rights could turn into bitter quarrels. Nevertheless citizens of eastern Idaho working with common purpose and cooperation succeeded in creating a stable, lasting base for city prosperity and a bountiful empire of valley farms. Canals are user-owned and maintained, and the numerous and intricate canal systems of the entire upper valley are under the jurisdiction of Irrigation District No. 1 of the state of Idaho, with headquarters in Idaho Falls.

Anderson Canal

John C. Anderson had joined his brother Robert in the toll- bridge business in 1872. In 1879, he launched an irrigation project by hiring surveyor J. H. Martineau to stake out a canal from Snake River.

"Jack Anderson is constructing an immense canal taking the water from Snake River about 25 miles above and bringing it over a large section of the country comprising thousands of acres which will be about 25 miles in length and cost from 25 to 30,000 dollars," according to the "Register" in November, 1880.

In the meantime, George and Robert Smith had chosen homesteads near where Snake River emerges from its canyon--the later Poplar community. They had claimed a likely place to coax water from the river and succeeded in digging a canal to water their crops in 1880. Anderson Brothers, doing business as Snake River Water Company, negotiated with the Smiths for their river site, and proceeded with their canal project.

In 1887, Snake River Water Company stockholders sold their canal and water rights to Eagle Rock and Willow Creek Canal Company. For several miles from the river, the canal continued to be known as the Anderson, and a low retaining dam built across the river in 1902 bears the name Anderson Dam.

Eagle Rock and Willow Creek Canal; Progressive Irrigation District.

Homesteaders along Willow Creek saw plainly that they needed additional water from Snake River to augment the flow of the creek, which branched into three channels and could serve hundreds of acres of potential farms. In 1884, they organized the Eagle Rock and Willow Creek Canal Company, and claimed a river site a few miles below the Anderson Canal heading. Stockholders dug a canal to reach Willow Creek.

In 1887, this canal company purchased the rights and facilities of Andersons' Snake River Water Company and joined the two canals near the mouth of Willow Creek canyon--a few miles below the later Ririe Dam. These and small canals such as the Hillside, Gardner and others branching from Sand Creek and other side channels, were later incorporated into the Progressive Irrigation District for management and distribution, with business offices in Idaho Falls.

Farmers Friend Canal; Enterprise Canal. The Farmers Friend Canal first brought water from the river to Poplar in 1884, and later was extended to Shelton, Milo, and Ucon. The smaller Enterprise, constructed 1890-1894, served more of the same area.

Porter Canal.The notion of "flour gold" flowing in the waters of Snake River in the 1880s sent adventurers, businessmen and off-duty barkeepers scurrying to claim sites for sluices and other touted "gold-saving machines," according to numerous items in the "Register." Much gold was recovered, operators proclaimed--without verification--and the fever waned.

The Maclean Gold Mining Company filed on water and placer mining claims in 1886, and dug a canal close to the west side of the river near Eagle Rock. Besides the mining activity, irrigation water was furnished to a few developing farms downriver. In 1887, a Denver financier became owner through mortgage default. In 1893, the Great Western Canal Construction Company acquired the holdings, including the canal which still runs through the city's west-side motel row and bears the name of the absentee invester, Henry M. Porter.

Woodville Canal. The young men from Hooper, Utah, who eyed unclaimed land south and west of Eagle Rock in 1888 had no money, but unbounded ambition. They brought their families the following year and commenced the ongoing miracle of turning sagebrush into homes and farms. A great expanse of cedar-grown lava crevices lay along the west side of the tract. It was a nature-given resource to cut for fuel and to trade for needed commodities. Woodville seemed an appropriate name for the community.

A canal taken from the river three miles below Eagle Rock could be directed to the farms, it was thought. George Gifford used a surveying instrument made with a spirit level to stake out a course for the canal. To be safe, the settlers brought in surveyor Joseph A. Clark from Eagle Rock. He found the grade correct with only a few changes. Also, he took his pay in cedar wood. Another good market for the cedar was the flour mill on the west bank of the river at Eagle Rock, where wood was used to fuel the steam- powered roller mills. Farmers could take flour for pay, and trade surplus flour for other supplies.

George Gifford was elected president of the Woodville Canal Company, and water stock was issued to pay for labor in building the canal and ongoing maintenance. By the spring of 1893, water to supply 3000 acres was turned into the canal. Other early homesteaders included Matthews, Kerr, Messervy, Taysom, Hammer and other families.

The Idaho Canal. In 1890, when Idaho became a state, Eagle Rock was blossoming into the city of Idaho Falls. High hopes abounded. Joseph A. Clark, C. C. Tautphaus, Nels Just, DeForest Chamberlain, Casper Sauer and other area promoters, with Lucius Hall of Salt Lake City and unnamed Chicago backers, incorporated the Idaho Canal Company "to construct and own canals, and acquire water rights, to take water from Snake River for the purpose of agriculture, manufacturing and mining."

Tautphaus deeded to the company a site and 1889 water claims near Bear Island, ten miles upriver from town. To bring water to thousands of acres as proposed, freighter-turned-homesteader Nels Just contracted to dig the huge canal. With his eighteen-year-old son James, Nels supervised a large crew who worked with slip scrapers and three primitive graders drawn by twelve horses. When that large project was completed, the company acquired a second site and water rights close to other canal headings near the mouth of the Snake River canyon, and later, downstream on the main river, a headgate site to supply irrigation water to the Indian reserve lands.

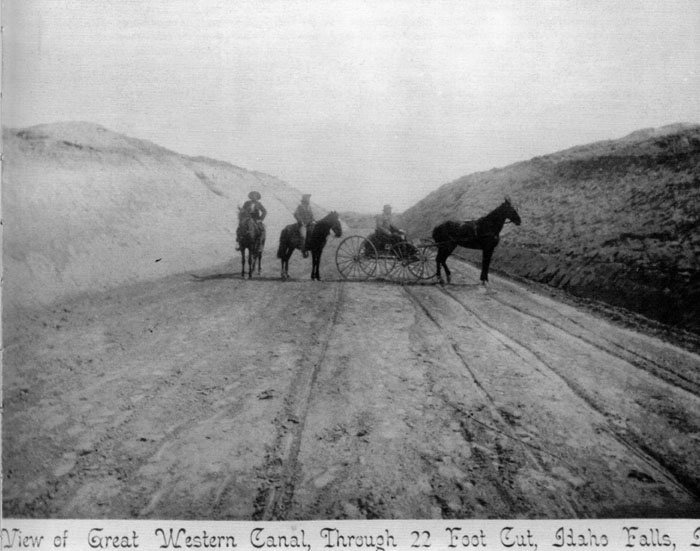

Great Western Canal Company. Promoter Bernard McCaffrey filed on Snake River water rights in 1891. As Great Western Canal Construction Company, he also acquired the holdings of the Porter Canal Company in 1893. After various name changes and shifting of eastern financial backing, Great Western Canal and Improvement Company owned McCaffrey's interests as well as thousands of acres of potential farming ground. Promoters claimed the company spent four million dollars building canals and acquiring land titles. This company sublet the project of bringing in settlers.

The new company recruited mostly hardworking farmers of Swedish heritage, who arrived in Idaho in 1894 and succeeding years. As in all pioneering, problems were legion. Worse, the Swedes found they had been swindled by the land company, though litigation later alleviated some of the inequity. The Swedes stayed on, and gradually assumed ownership and management of the Great Western Canal Company and smaller units which it absorbed. Notable Swedish pioneers included Burkman, Lundblade, Anderson, Lundgren, Melquist, Peterson, Swanson, Johnson, Beckman, Nelson, Erickson, Carlson, Hanson and other families.

The Great Feeder. Downriver from early canal diversion points at the mouth of Snake River canyon, a smaller south channel runs parallel to the river some thirty miles. Settlers tapped this water source for many canals including Harrison, Burgess, Rudy, Rigby, North Rigby, Butler Island, Clark and Edwards, Lowder and Jennings, East Labelle and others. But river currents veer, and during the summer of 1894, the side channel, dubbed the Dry Bed, ran scant. Frantic water users tried to no avail to build diversion dams to feed the channel.

Pooling their resources, patrons incorporated the Great Feeder Canal Company on January 1, 1895, and launched a project of heading a huge canal a half-mile upriver to divert water into the Dry Bed. The finished headgates were touted as the largest in the world, and a gala celebration in June marked the opening. Surveyor Joseph A. Clark, active in the project from the beginning, was on the program, along with Editor William E. Wheeler and area notables Thomas E. Ricks, Charles Ellsworth, R. L. Bybee, J. A. Webster, R. F. Jardine, Josiah Call, H. M. Perry, and J. P. Davis.

Changing water currents of later years made necessary the building of larger diversion structures.

Dams Across Snake River

Canal users learned to cope with breakout and sinkhole disasters, but changing river currents and unstable seasonal water flows presented constant and critical challenges. In 1900, stockholders of the two big canal companies drawing water a few miles upstream from Idaho Falls pooled their efforts to replace previous rockfills with a low dam. Designed to divert a steady supply of water to the Idaho Canal on the east and the Great Western on the west, the project was supervised by August Erickson and E. J. Hall, with Lem. J. Hall as foreman.

Working in the water, drillers made holes in the solid lava bottom of the river for anchor bolts for the dam's foundation. The bolted-down framework was then filled in with tons of huge boulders. Three-inch plank faced the dam, and a plank deck covered the 944-foot span. In about 1912, a reenforced concrete dam was constructed behind the rock dam, which was left in place.

Porter Dam. August Erickson and the Halls repeated their dam-building success in 1901 by contracting to build a barrier to divert water into the old Porter Canal. Using their equipment from the previous year, they constructed the Porter dam of squared timber of dimensions up to 12 by 12 inches for framework, and using rock cribs for deeper channels. This dam ensured adequate water to feed into the Great Western system.

The Idaho Falls Canal. The new century spawned ambitious dreams. Mayor Joseph A. Clark, with his council, began plans for a canal to generate power for the town. By 1901, Perham Brothers Contractors completed digging a canal to an admirable spot for a generator.

Upstream from Idaho Falls, the canal diverted water from the river by means of a rock crib diversion, and coursed southeast to low ground in the area of the later A. H. Bush school. A small lake formed here, from which water could be released as needed for the generator. The canal continued southeast to cross the railroad tracks and reach First Street, where it veered south. The Canal Builders excavated the broad expanse which later became Boulevard down to Tenth Street. Here at the bottom of a slope, workers installed a 125 horse-power generator, and the town was in the electrical power business. Over one thousand dollars was collected the first year. The canal water was diverted into Crow Creek below the generator to be returned to the river.

This power plant was replaced in 1911 by a new generator installed on the river at Eagle Rock Street. The canal was covered over in about 1914 and Boulevard opened for traffic. A small park on the west side, near the intersection of 9th Street, marks the site of the original generating plant.

An excerpt from City Council minutes June 12, 1914, explains when and why Boulevard north of 10th was opened as a street:

- To the City Council:

- As our new power unit is about completed, and the old City Plant has been out of service for some time; and as the flume is rotting away and likely to go out at any time; and as a further continuance of the City Canal will necessitate new bridges and other repairs which will mean a big expense to the City; and as a ditch-rider is necessary all the time when the canal is in operation, being one more salary on the City's pay-roll; and as the day is fast coming when a covering to the Canal will be necessary to protect life, on account of the treacherous banks; and as the whole canal only means one hundred twenty-five horse-power, and the same investment would install four hundred horse power at the river; I recommend that Boulevard be opened as a street from the old power house to the coal-chutes. This will not jeopardize any valuable rights, and, at the same time, will make a much needed improvement. I trust this recommendation will meet with your hearty approval. Barzilla W. Clark, Mayor

Osgood Project. The gently rolling land north and west of Idaho Falls lay too high above the river for a gravity canal, but appeared well-suited for the newly developing system of alternate years of fallowing and planting--dry-farming. The Idaho Falls Dry Farm Association claimed seven thousand acres in 1904 and began to cultivate the area. H. C. "Bud" Frew directed large crews who used fifty teams of horses to plant and harvest.

Moving in a new direction in 1914, A. T. Shane, J. L. Milner, W. L. Shattuck, L. W. Hartert and George Brunt, all of Idaho Falls, launched the Osgood Irrigation Project. They built two small reservoirs in Jackson Hole to furnish water to be taken out downstream where it was pumped thirty-five feet up to a canal. Joe Marshall surveyed the contour canal following ridges. Crews worked with dozens of horses to construct the canal system. George Brunt served as general manager of the project. First returns were meager, but improved with good cultivation practices. In 1919, Utah Idaho Sugar Company purchased the tract and expanded it to ten thousand acres. Don C. Walker, superintendent, staked out many of the canals and laterals. It was said that he could survey, unerringly, by sight. The sugar company gradually sold the land to individual farmers.

Submitter: Edith Haroldsen Lovell

Primary Sources: Daughter of Utah Pioneers, Pioneer Irrigation,

Upper Snake River Valley, compiled and edited by Kate B. Carter,

1955.

Idaho Falls City Council Minutes, 1914; Sanborn maps, 1911.

Files of Edith Lovell, who is author of Captain Bonneville's

County, Idaho Falls, 1963. She has written for the Post Register,

special editions as a historian, and for Eastern Idaho Farmer, and

published many articles.

CONTENTS

Begin HereIntroductory Comments

- Chap. 1 - Agriculture

- Potatoes, grains, sugar beets, livestock, irrigation.

- Chap. 2 - Business and Industry

- Banking, Chamber of Commerce, Rogers Brothers Seed.

- Chap. 3 - Amusements, Arts and Music

- Amusements: dancing, circus, baseball, theaters, Heise Hot Springs, War Bonnet Roundup, parades. Arts: painting, drama, dance, music, symphony, opera theatre.

- Chap. 4 - Communications

- Newspapers, telephone, broadcast.

- Chap. 5 - Celebrations

- Centennials and Jubilees, Pioneer Day, Intersec.

- Chap. 6 - Churches

- Chap. 7 - City Government

- Mayors, City Hall, Public Library; Departments of Electricity, Fire, Police, Building and Planning, Parks and Recreation, Public Works.

- Chap. 8 - Courthouse and Federal Post Office

- Chap. 9 - Historic Preservation Efforts

- Bonneville County Historical Society, Idaho Falls Historic Preservation Commission (Historic buildings, places, homes), Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

- Chap. 10 - Schools

- Chap. 11 - Clubs/Fraternal Organizations

- Lodges, Sportsmen's Association, American Legion and other Veterans Associations, Boy Scouts.

- Chap. 12 - Transportation

- Railroad, Automobiles, Aviation.

- Chap. 13 - Medical Practice &Amp; Hospitals

- Chap. 14 - Native Americans

- Chap. 15 - Snake River

- Bridges, Greenbelt, Temple.

- Chap. 16 - Tourism and Hotels

- Chap. 17 - Lawyers and Judges

- Chap. 18 - War Efforts

- Red Cross, World War I, World War II.

- Chap. 19 - Population Growth

- Chap. 20 - INEL

- Appendix 1 - Bibliography Guide

- Appendix 2 - Chronology